Irons in the Embers: Still burning after all these years

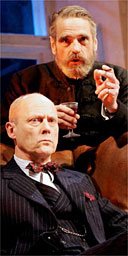

| Our anniversary weekend trip to Venice was the first time in ten weeks Flame-Haired Angel hadn’t awoken at 4:30am to take the Eurostar from Paris to London. She had been doing a course in costume design at Central St Martin’s, near Red Lion Square. The last weekend she had her course, we made a junket of it together. She didn’t know when she’d next return to London, and, conveniently, I had to be there for a conference the following week. We had a ball just hanging in London -- going to pubs, seeing friends, bingeing on the National Portrait Gallery -- but one of the really remarkable doings was a rainy Saturday afternoon spent at a play at the Duke of York’s Theatre in the West End. Flame-Haired Angel had bought the tickets on a whim for our getaway weekend. It wasn’t entirely unselfish. She has a thing for Jeremy Irons. And so it came to pass that we got to watch him for two hours, from four rows back, in a play called Embers, and both of us were awed. I’ve since read reviews that placed the production anywhere from rotgut to not bad, but we came away distinctly more impressed and thoroughly sated.  The play is notable for a single attribute more than any other: It’s virtually a soliloquy. Irons, who has apparently been off the stage for some years, chose for his return a showcase of virtuosic solo skill. There are two other actors, but one has less than five minutes work and the other, while on stage much of the play, spends most of it listening to Irons’ character give voice to decades of struggle. The play is notable for a single attribute more than any other: It’s virtually a soliloquy. Irons, who has apparently been off the stage for some years, chose for his return a showcase of virtuosic solo skill. There are two other actors, but one has less than five minutes work and the other, while on stage much of the play, spends most of it listening to Irons’ character give voice to decades of struggle.Watching and listening to Irons, I was struck by two things. First, there are few other actors who wouldn’t have hypnotized me into a soporific stupor in this role. Yet, Irons’ intensity, dynamic range and crackling restrained energy kept both Flame-Haired Angel and I riveted. It was like watching a skilled gymnast. And that’s where the second thing comes in. His performance was very, very British, and very un-method. Stanislavsky and Lee Strasberg would have hated it. “The method,” as taught by Strasberg in The Actors Studio, building on principles set out by Stanislavsky, aims to make the performance and the actor completely transparent, so all that is left is the character, present with such verisimilitude that you forget there is a performance at all. Folks like De Niro, Brando, Keitel, Julia Roberts are all method actors. The approach of British-trained stage actors has always been different. It is often (and often disparagingly) called more theatrical. While I’m never quite sure what “more theatrical” means, British actors on stage seem less to disappear inside their characters, and more to present them to the audience. Given the audience has limited time to grasp the character aspects that are fundamental to the plot and relationships of the play, a British actor will take essential bits of the character’s personality and behavior and amplify them. Sometimes, these amplifications are so striking, they don’t look all that much like day-to-day behavior, and it is in these moments that the performance, and therefore the presence of the actor, is obvious. There are whole books on this, and it’s not a topic that interests me all that much. Never mind the debate about genres of theatre and which types of play are better suited to which type of acting. The reason I bring up the trans-Atlantic debate surrounding acting craft is that Irons’ performance was a tour de force example of the British school. You never for a moment forgot you were in a theatre watching a play. Irons drew his character in sharp outlines, so as to create a bas relief of the protagonists’ humanity: more than 2-dimensional, but not fully 3-dimensional. I found the approach freeing and honest. In a strange way, the clarity of the performance, and the lack of conceit about the presence of the actor dispenses with the notion that all the production’s energies should be focused on helping the audience suspend disbelief. Instead, energy is given over to pointing our attention at other -- perhaps bigger -- things: for example, the themes, questions and particular world-view the play exists to explore. To put it plainly: I don’t have to believe that a person on stage has *actually* died in order to understand the impact of the death on the other characters. So, why should the actors’ craft be poured into achieving completely transparent reality when I’m not going to believe the death, anyway? I am, after all, sitting in the Duke of York’s Theatre, next to my wife, on a rainy Saturday afternoon. That’s a stage. That’s an actor. He is not dead. What I want, as an audience member, is for the death to be believable enough that its fallacy doesn’t distract me from its impact, its effect.  As it happens, Irons’ character doesn’t die in the play. Nor does anyone else. And, I’m glad to say that no actors died on stage. What these actors did do was present their characters boldly, exaggerating each mannerism just enough for us to see what we were being told with the semiotics of gesture and posture and movement and timbre and every other tool the actor has at his disposal. Irons, specifically, used his voice like a bouncer’s arm to lift the audience, as a whole, bodily from our seats. (Even as someone who’s often complimented on my voice, I listened envious of his.) As it happens, Irons’ character doesn’t die in the play. Nor does anyone else. And, I’m glad to say that no actors died on stage. What these actors did do was present their characters boldly, exaggerating each mannerism just enough for us to see what we were being told with the semiotics of gesture and posture and movement and timbre and every other tool the actor has at his disposal. Irons, specifically, used his voice like a bouncer’s arm to lift the audience, as a whole, bodily from our seats. (Even as someone who’s often complimented on my voice, I listened envious of his.)And, of course, as he carries 95% of the lines, his lifting is impressive, indeed. I left the theatre baffled that I could have hung so on his every word for so long in a darkened room. A marvelous performance. I should mention, before closing this theatrical note, that our week was also full of Shakespeare, but Shakespeare of the sexy Kentuckian (!) variety. We crashed at her place on Saturday night, and met up again to approve her new boy mid-week. She was just fucking glowing. And it hain’t nothing to do with seeing so much of us. It was one of those un-hide-able projections of joy that comes from finding something you’ve been looking for a long, long time. .. |

Comments on "Irons in the Embers: Still burning after all these years"

-

Anonymous said ... (9:53 AM) :

Anonymous said ... (9:53 AM) :

post a commentWow!

*blushes*